Many solutions require more than pixels

Purchasing decisions are driven by emotion, but those highs and lows are amplified when a potential career change is involved. While Bloc was saddled with a dysfunctional educational product, the curriculum was only part of the problem.

Designer Track | 2015 - 2016

When I joined Bloc in 2014, I entered a thriving landscape. The company had pioneered the future of technical bootcamps, condensing a learning experience into 12 short weeks before sending students off to find employment. The twist was that Bloc's approach was entirely online, a unique factor that opened up a broad market of potential students. Early press coverage helped fuel the momentum.

However, the excitement masked a fundamental issue: 12 weeks wasn't enough time for most students to become employable. Bloc recognized this early on, and since the company guaranteed employment to graduates (or offered a refund), something needed to change to protect both the student and the company.

In response, Bloc introduced ‘Tracks’ in 2015. This new model featured tailored versions for Developers and Designers, essentially connecting existing courses in a coherent pathway. The shift was immediate; students gravitated towards Tracks, undeterred by the longer time frame or higher price point. They recognized the enhanced value.

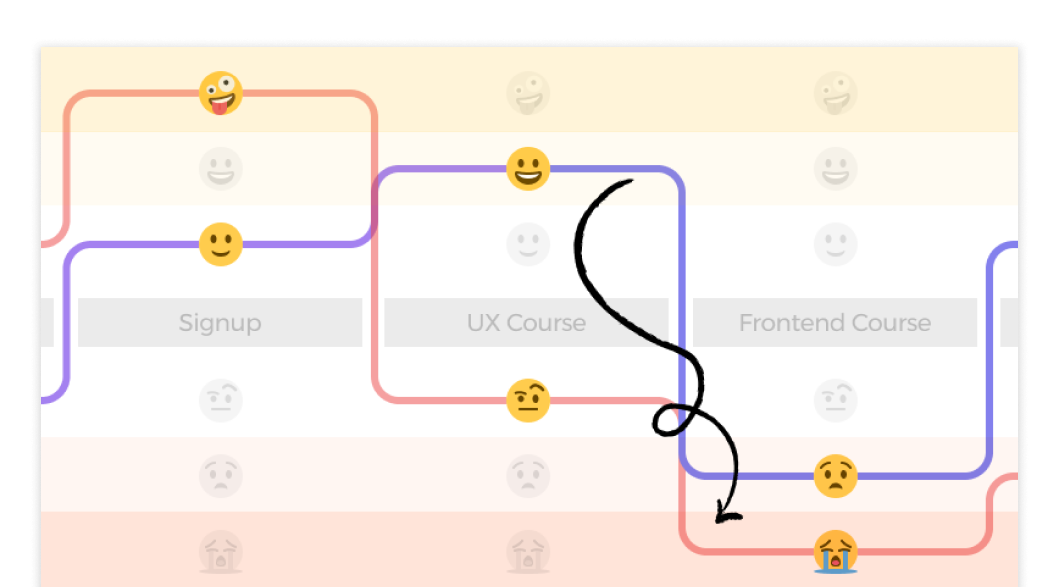

Yet, not all was smooth sailing. While both Developer and Designer Tracks were popular, the latter revealed a fundamental flaw. Constructed to lead students from traditional UX Design to front-end courses, the Designer Track suffered alarming dropout rates during the transition. Roughly half of the students were leaving soon after beginning the front-end coursework.

After a few months, Bloc pulled the Designer Track from its offerings. At the same time, a change in leadership cast a shadow over the Design-related products. Sales were dwindling, and it became questionable whether Bloc would continue to offer them.

Initial objectives

- Determine source of dropoff at front-end

- Why is this an emotional rollercoaster for users

- Audit current curriculum for consistency

- Interview students afrom each program phase

Step 1: Internal Discovery

While at Bloc, I firmly believed our design offerings should be on par with our development programs. Despite this conviction, the initial challenge lay in the underwhelming sales figures for the design courses. Yet, I held the belief that with the right adjustments, our design program could not only match but excel beyond our development programs. The primary objective? Deeply understanding our customer's motivations and expectations.

Beyond Surface-Level Examination

To truly understand the intricacies of our program, a thorough investigation was imperative. This involved interviewing mentors, students, and members from the sales and customer service teams. Additionally, I delved into a comprehensive review of the courses within the Designer Track curriculum. While I initially suspected the curriculum was the main issue, my research did indicate areas for improvement.

Finding the Path Forward

The insights I gathered were multifaceted. While analyzing my notes, it was evident we faced both internal and external challenges. Crafting a comprehensive solution was formidable, especially since the optimal route seemed to entail significant structural changes within the company.

Step 2: Navigate the Turf Wars (and Legal Gray Areas)

To get where we needed to go required quick decision-making, the ability to navigate legal challenges, and a willingness among all parties to become part of a larger collaborative team. On top of that, we needed to address a divisive industry issue that was taking root within the company. Doing so, would allow us to pivot the program and ultumately align with where the industry was moving.

Internal Debate

It was 2015 and the tech world was ablaze with one hotly contested question: Should designers code? This disagreement was not just an external debate but was bleeding into our product, affecting the way we taught design at Bloc.

Team Review

Because our mentors were contractors, I couldn't legally dictate how they taught the course. Our attempts to expand design were faltering, plagued by differing opinions about what was needed to become a professional designer. Recognizing the need for immediate action—faster than company policy changes allowed—I quickly assembled a team of allies. I began by reviewing the skills of our 30 design mentors, leveraging my knack for evaluating talent.

Assembling a Core Team

From our pool of mentors, a handful both taught UX and were passionate about front-end development. Conflicts reduced that number further, but a core team consisting of myself, Zach Lebar, Alissa Likavec, and Terry Million was formed. This team was enough to refactor the existing curriculum and restructure the Designer Track. Over three months, we fostered strong camaraderie and built a shared conviction around concepts we believed would best prepare designers for employment. Our decision was later publicly confirmed as correct for the era by the March 2017 Design In Tech report from John Maeda.

Step 3: Resetting Expectations

Now that we had a core team aligned on our delivery approach, we focused on addressing the top of the sales funnel. This involved supporting key sales and marketing initiatives.

New Friends in Sales

Through careful discovery work, we found that our teams were receiving two types of inbound leads: complete tech newbies and adjacent field designers who were upskilling. The latter rarely posed a problem, while newbies showed great enthusiasm but were also more likely to drop out.

It became clear that a delicate balance was needed with our sales team. We allowed pushing for the sale but used professional experience to manage expectations. By focusing on real impacts rather than lofty salary promises, we helped clients approach the program with clear-eyed realism.

Camaraderie with the sales team enabled us to turn calls over to them. We trusted they wouldn't overpromise, and they knew our team would respond quickly. Alignment in goals made collaboration effortless.

Early Student Interactions

An upfront investment in each potential student helped eliminate poor outcomes quickly. We tackled the common issue of non-commitment by injecting prework requirements at the program's onset, effectively weeding out those unlikely to finish. For students who were actively employed, our early numbers showed that those failing to finish prework tasks were three times more likely to drop out later. Thus, we recognized that what seemed like busy work was, in fact, a crucial step.

As most people trying Bloc in 2016 were experiencing remote learning for the first time, proactive community support became central to the user journey.

Reducing Buyer's Remorse

We noticed that sign-ups furthest from the start date were most likely to experience buyer's remorse. We hypothesized this was due to excitement followed by a significant waiting time. Therefore, immediate onboarding and community access were provided, with a mentorship team ready to greet them.

Step 4: Supporting Structure

With the core team unified in our approach, we could now collectively address the larger program's structural issues.

Rough Patches Happen

Learning something new is hard, but offering the support needed to make it through isn’t really hard. Having identified the top areas where students were having problems, the support mechanisms added ensured that a full-time mentor would be checking on them. Additionally, this assisted mentors in identifying both possible problems and solutions as the communication internally was also enhanced.

Outcome Consistency

The initial challenge was ensuring consistent outcomes for students. The prior system matched students with mentors throughout their learning journey, with changes only occurring upon complaints. Our revised model segmented the program into gated sections. To advance, students had to pass evaluations administered by core team members, namely Zach, Alyssa, Terry, or myself. This allowed us a clearer view of the student journey in real-time, providing key insights at crucial stages.

Rethinking Mentorship

The existing mentorship system was not adequately serving our mentors, primarily those working part-time. They were not readily available to address student inquiries constantly. Recognizing the increasing need for student support between mentor sessions as the program expanded, we bolstered our community channels with paid assistance. This ensured timely help was available for all students when they needed it.

Outcomes

A significant part of our success is owed to the unwavering support from our leadership. Courtland Alves, stood out particularly for his encouragement. He urged me to trust my instincts and to treat the program as if it was personally mine. Given that Bloc had more developers than designers, few had a say in our decisions, putting the responsibility of success or failure squarely on our shoulders.

Team Structure and Expansion

Our start was modest, with only two students enrolling in the initial month. However, the subsequent 12 months saw an exponential increase in interest, necessitating an expansion of our team and support structures to cater to the growing demand.

Growth and Financial Impact

By the time Bloc was acquired in 2018, our Designer Track program accounted for an impressive 35% of the company's monthly revenue.